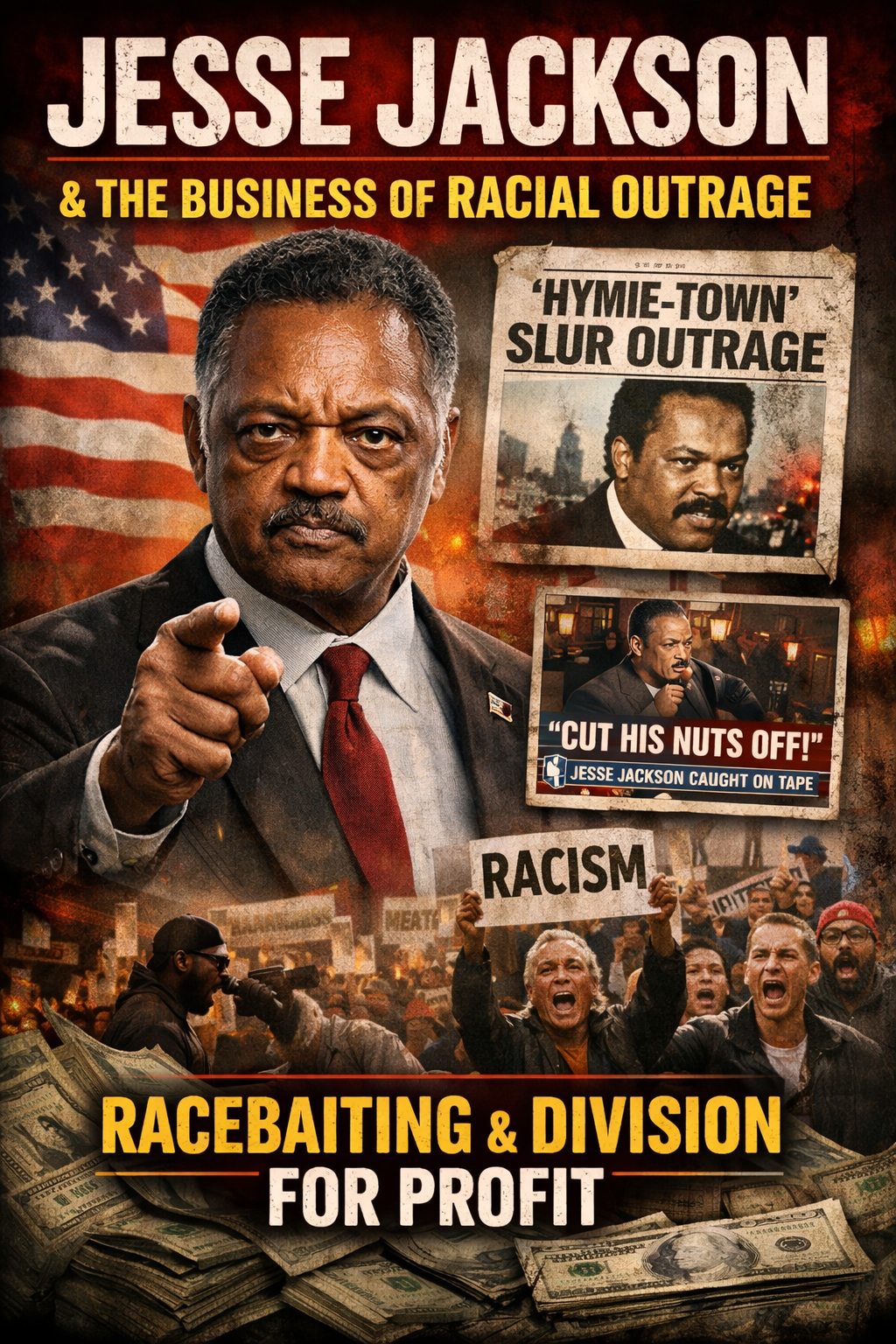

Jesse Jackson and the Business of Racial Outrage

Racebaiting and Division for Profit

Introduction

Jesse Jackson just died (February 17, 2026), and like clockwork the tributes roll in: “icon,” “giant,” “trailblazer,” “civil-rights hero.” Some of that is true in the narrow sense that he was there, he was visible, and he helped mobilize people.

But I’ve never been able to separate Jesse Jackson the historical figure from Jesse Jackson the political operator—the man who made a long, lucrative, decades-long career out of keeping America emotionally stuck on race. Not solving it. Not healing it. Not moving people toward shared rules and shared citizenship. Keeping it hot.

That’s what I mean when I say “racebaiting.” Not “talking about racism,” not “acknowledging history,” not even “advocating for Black Americans.” I mean the habit of taking every social tension, every hardship, every disagreement, and turning it into an identity grievance machine—because grievance is power, grievance is fundraising, grievance is relevance.

If you think that’s harsh, fine. I’m not asking anyone to adopt my view. I’m asking you to look at the record and ask a simple question: did Jackson’s style reduce racial temperature over time—or did it monetize it?

What “racebaiting” looks like in real life

Racebaiting isn’t always a single dramatic moment. It’s a pattern.

It’s using moral language like a club.

It’s implying disagreement is bigotry.

It’s making yourself the referee of who’s “authentically” Black, “properly” allied, or “on the right side of history.”

It’s turning politics into permanent group conflict, where the public is trained to interpret everything through race first, facts second, and character last.

Jackson was brilliant at that kind of politics.

He was a gifted speaker, a master of symbolism, and a natural at positioning himself at the center of the story. Even friendly retrospectives note the “controversies” and the self-promotional tendencies that followed him.

The moments that give the game away

The “Hymie/Hymietown” scandal wasn’t a “gaffe.” It was a tell.

In 1984, during his presidential run, Jackson used the slur “Hymie” for Jews and referred to New York City as “Hymietown.”

The comments came out through reporting in The Washington Post and set off a national firestorm.

You can call it a mistake. You can say he apologized. You can say it was “off the record.”

But here’s what I take from it: this wasn’t a teenager mouthing off. This was a national civil-rights leader who was comfortable enough with ethnic contempt to speak it casually.

And it matters because it exposes something people don’t like admitting: “civil-rights leadership” doesn’t automatically equal moral clarity. Sometimes it equals political leverage. Sometimes it equals a license to say ugly things while still being treated as a saint.

The Obama “nuts” comment was more than crude—it was tribal enforcement.

In 2008, Jackson was caught making a crude remark about Barack Obama (“I want to cut his nuts out/off,” reported widely at the time), followed by an apology.

Again: you can call it a hot mic moment.

But I see it as a glimpse into the internal policing that identity politics creates. Jackson didn’t just disagree with Obama’s messaging. He expressed it as personal humiliation—an attempt to drag, diminish, and punish.

That’s not “leadership.” That’s dominance behavior dressed up as moral authority.

A career defined by dividing lines, not shared lines

Even the more respectful biographies describe Jackson as a figure who inspired millions, built organizations, ran historic campaigns, and also carried a constant trail of tensions and controversies.

I’m not arguing he never did anything useful. I’m arguing that the style he made famous—permanent racial framing as the master key to American life—has downstream consequences:

- It trains people to see themselves as members of tribes first, citizens second.

- It turns outcomes into identity scoreboards, not problems to solve.

- It rewards the loudest grievance entrepreneurs and punishes the reformers who try to build coalitions.

If your whole political identity is “America is structurally racist and here’s today’s proof,” then you can never allow the situation to truly improve—because improvement reduces the market value of your role.

That’s the industry. Jackson was one of the early masters of it.

To be fair: what people admire about him

If you admire Jesse Jackson, you’re not crazy. He was close to Martin Luther King Jr., he was present at major moments of the civil-rights era, and he built organizations (Operation PUSH and the Rainbow Coalition) that pushed economic and political participation.

He also ran serious presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988 that broke barriers and expanded what was politically imaginable in the U.S.

So yes—history will mark him as significant.

But significance is not the same thing as goodness. And “helped mobilize people” is not the same thing as “helped heal the country.”

My bottom line

In my view, Jesse Jackson’s long-term legacy is less about civil rights progress and more about normalizing a politics of accusation—where race becomes the default lens, the default weapon, and the default explanation.

That approach keeps people angry, suspicious, and psychologically outsourced. It gives them a villain. It gives them a script. It gives them a reason nothing is ever their responsibility.

And it creates exactly the kind of society where opportunists thrive—on every side—because emotionally divided people are easy to steer.

If that’s “justice,” it’s a strange kind: one that never seems to arrive, but always seems to need another donation, another march, another headline, another outrage.

Why This Matters

If we want a country that actually holds together, we have to stop rewarding the grievance economy—whether it’s preached from a pulpit, shouted from a campus, packaged by a nonprofit, or sold by a media outlet.

You can acknowledge history without living inside it.

You can address discrimination without turning every issue into tribal war.

And you can pursue equal rights without needing a permanent class of professional referees who get paid to keep the temperature high.

That doesn’t mean pretending racism never existed or doesn’t exist. It means refusing to let race become the only story we’re allowed to tell—especially when some people have built entire careers telling it in the most combustible way possible.

References

Reuters. (2026, February 17). Jesse Jackson, civil rights leader and US presidential hopeful, dies at 84.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2026). Jesse Jackson.

The Washington Post. (1984, March 1). The Cost of Jackson’s Slur.

The Washington Post. (1984, August 16). Reporter Talks to Black Press on “Hymie” Remark.

The Guardian. (2008, July 10). US election 2008: ‘I want to cut his nuts out’—Jackson gaffe…

6abc / Associated Press coverage. (2008, July 10). Jackson apologizes for crude comment about Obama.

The Washington Post. (2026, February 17). Jesse Jackson, a leading African American voice on global stage, dies at 84.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this post are opinions of the author for educational and commentary purposes only. They are not statements of fact about any individual or organization, and should not be construed as legal, medical, or financial advice. References to public figures and institutions are based on publicly available sources cited in the article. Any resemblance beyond these references is coincidental.