God on Trial: Day 10

The Bible on the Stand

Introduction

For centuries, the Bible has been presented not merely as a sacred text, but as the Word of God - divinely inspired, infallible, and authoritative over all human affairs. Billions have accepted it as the ultimate standard for morality, the blueprint for life, and the direct voice of the Creator. But in this courtroom of reason, the Bible is not a witness to be believed on reputation alone. It is the defendant, and it must face cross-examination.

And when we examine the record closely, the evidence is not flattering. In fact, it’s damning.

The Contradictions That Can’t Be Waved Away

Believers often assert that the Bible is a unified, harmonious work. Yet even the opening chapters reveal that it can’t agree with itself. In Genesis, we have two conflicting creation accounts:

- In Genesis 1:24–27, animals are created before humans—culminating in man and woman being made together on the sixth day.

- In Genesis 2:18–19, Adam is formed first, then the animals, and later Eve from Adam’s rib.

Apologists try to smooth this over by claiming one account is “poetic” and the other “literal,” or that one is simply a “different perspective.” But in any court of law, two eyewitnesses who contradict each other on basic timelines would be considered unreliable.

The contradictions don’t stop in Genesis. The four Gospels—supposedly inspired accounts of the same events—disagree on:

- Jesus’s genealogy (Matthew traces his lineage through Solomon, Luke through Nathan—two different sons of David).

- The sequence of events during Holy Week.

- Who discovered the empty tomb, when, and under what circumstances.

These are not tiny footnote-level differences—they’re central to the story. If God truly inspired every word, why would such core facts be inconsistent?

Failed Prophecies and Scientific Errors

If a text claims to be the perfect word of an all-knowing God, it should not be riddled with failed predictions or scientific misunderstandings.

Consider Ezekiel 26:14, which prophesies that the city of Tyre will be destroyed and “never be rebuilt.” Tyre was indeed besieged by Nebuchadnezzar and later by Alexander the Great—but today, Tyre exists as a thriving port city in Lebanon. This is not an obscure prophecy; it’s a falsifiable claim that simply didn’t come true.

Then there are the cosmological errors. The Bible describes the earth as immovable (Psalm 104:5, 1 Chronicles 16:30) and depicts the sky as a solid dome (Genesis 1:6–8). The moon is referred to as a “light” in Genesis 1:16, when in reality it’s a non-luminous body reflecting sunlight.

These statements may reflect ancient Near Eastern cosmology, but if God is truly the author, are we to believe He didn’t know basic facts about the physical world He supposedly created?

Moral Failings in the “Good Book”

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the Bible is not its contradictions or factual errors, but its moral prescriptions—many of which we now consider barbaric.

- Slavery: Leviticus 25:44–46 explicitly allows the Israelites to own foreigners as slaves, passing them down as property to their children.

- Capital punishment for minor offenses: Numbers 15:32–36 prescribes death for gathering sticks on the Sabbath.

- Genocide: In 1 Samuel 15:3, God commands Saul to “kill both man and woman, infant and nursing child, ox and sheep, camel and donkey” in the Amalekite city.

Believers often defend these passages by appealing to “cultural context” or claiming that the New Testament supersedes them. But if morality is absolute—as many Christians argue—then why would God’s laws change depending on the century or political climate? And why would an all-good God ever command the slaughter of infants?

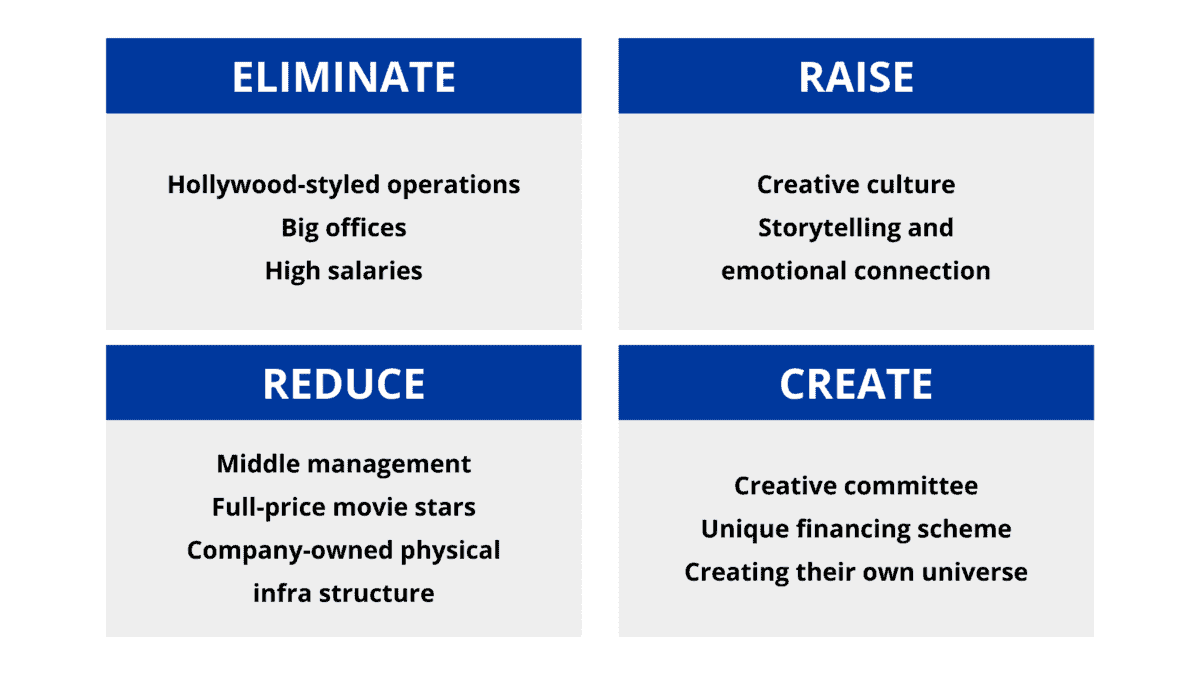

The Problem of Translation and Editing

Even if one grants that the Bible was originally perfect, the way it reached us is anything but. Over centuries, it has been hand-copied, translated, and edited by human beings with political and theological agendas.

- The Council of Nicaea (325 CE) didn’t just debate the nature of Christ; it played a key role in solidifying which books would be considered canonical.

- Many apocryphal texts—like the Gospel of Thomas or the Gospel of Mary—were excluded, not because they were proven false, but because they didn’t fit the emerging orthodoxy.

- Translation choices have dramatically altered meanings. For example, the Hebrew word almah in Isaiah 7:14 means “young woman,” but it was translated into Greek as parthenos, meaning “virgin,” which became a cornerstone of the virgin birth doctrine.

If God wanted to preserve an unaltered, crystal-clear message for humanity, outsourcing it to centuries of politically motivated committees seems like a strange strategy.

Anticipating the Defense

Some believers sidestep these problems by saying the Bible is “metaphorical” rather than literal. But metaphor doesn’t part seas, turn water into wine, or make the sun stand still in the sky. These are concrete claims presented as history, and if they are not literally true, then they fail as evidence of divine intervention.

Others will insist we must understand “the heart” of the Bible. But “the heart” is a vague, malleable concept—one that allows every denomination, pastor, and believer to decide for themselves which parts to take literally, which to spiritualize, and which to ignore. In legal terms, that’s hearsay built on selective interpretation.

Why This Matters

Because the Bible remains a central influence in lawmaking, education, and culture—even in secular societies. When it is used to justify legislation on marriage, reproductive rights, or science education, the credibility of its claims becomes a public concern, not just a personal belief.

If we treat the Bible as a human product—written in a specific cultural and historical context, subject to human error—we free ourselves to build moral and legal systems on reason, empathy, and evidence rather than on the authority of ancient texts. That’s not an attack on faith; it’s a call for intellectual honesty.

Finally...

The Bible has had its say. We’ve examined its claims, its contradictions, and its unverified history. In any real courtroom, a book of anonymous, centuries-old testimonies wouldn’t be the smoking gun—it would be Exhibit A in how hearsay can masquerade as fact.

But a trial doesn’t end with the evidence on paper. Now, we turn to the people who swear it’s all true. They will take the stand, one by one—prophets, apostles, evangelists, and ordinary believers—each convinced their story proves God’s existence.

And like any good cross-examination, we’re about to find out if their testimonies hold…

or if they crumble under the weight of the simplest questions.

References

- Ehrman, B. D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperSanFrancisco.

- Finkelstein, I., & Silberman, N. A. (2001). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Free Press.

- McDonald, L. M., & Sanders, J. A. (Eds.). (2002). The Canon Debate. Hendrickson Publishers.

- Collins, J. J. (2004). Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Fortress Press.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this post are opinions of the author for educational and commentary purposes only. They are not statements of fact about any individual or organization, and should not be construed as legal, medical, or financial advice. References to public figures and institutions are based on publicly available sources cited in the article. Any resemblance beyond these references is coincidental.