Are We a Christian Nation?

Reconciling Faith, Freedom, and the Founders

Introduction: The Claim and the Conversation

The phrase “America is a Christian nation” is often repeated in political debates, church pulpits, and public discourse. To many, it’s a rallying cry—a call to return to moral roots and reaffirm faith-based values. But what does the statement truly mean? Is it a historical fact, a cultural observation, or a political ambition?

To answer honestly, we need to separate emotional appeals from historical reality. Yes, Christianity has shaped American life. But the Founders, in crafting a new republic, deliberately avoided establishing any state religion—even one they personally followed. Understanding this tension is key to preserving both religious liberty and national unity.

Christianity’s Influence on American Culture

There's no denying that Christian values played a significant role in shaping early American society. From the Puritans in New England to Quaker communities in Pennsylvania, Christian teachings on human dignity, charity, and moral order informed education, law, and family life.

Christian churches often served as early schools, meeting halls, and even political organizing centers. Biblical literacy was widespread, and references to Scripture appeared frequently in public speeches and private writings.

Our shared civic language reflects this legacy: “God bless America,” “In God We Trust,” and “Endowed by their Creator” are phrases that echo the nation’s religious DNA.

But this cultural inheritance, while important, is not the same as creating a Christian government. The Founders knew this distinction—and protected it carefully.

The Constitutional Reality: No Religious Test

The U.S. Constitution makes it crystal clear: the United States is a nation of laws, not religious mandates. Article VI explicitly states:

“No religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

The First Amendment goes further:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”

These clauses were groundbreaking. In a time when most European nations were entangled with national churches, the American republic dared to do something different: create a system where religion was private, voluntary, and protected—not imposed.

What the Founders Believed—And What They Feared

Many Founders were religious men. George Washington regularly attended church and spoke often of Providence. John Adams called religion essential to morality. But others—like Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin—were Deists, skeptical of miracles and wary of religious institutions.

What united them was not uniform doctrine, but a shared fear of religious tyranny. They had seen the chaos of Europe’s religious wars. They knew how power could corrupt even the holiest of institutions. As James Madison put it:

“Religion and government will both exist in greater purity, the less they are mixed together.”

(Madison, 1819)

Their goal was not to erase faith from public life—but to prevent government from favoring one faith over another. In their vision, religion would flourish precisely because it was free.

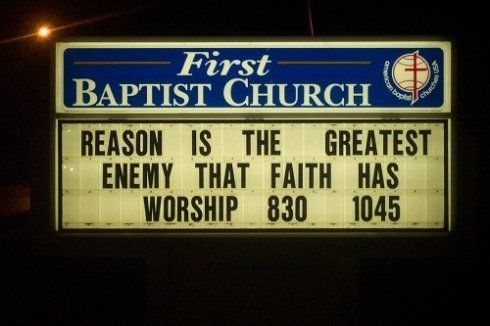

Fundamentalism and the Modern Political Divide

In recent decades, some Christian political movements have called for America to "return to its Christian roots"—often meaning laws that reflect conservative religious beliefs. These include stances on abortion, LGBTQ+ rights, school prayer, and curriculum control.

While these causes may be sincerely motivated by faith, they raise essential questions: Should one group’s interpretation of Scripture dictate law for everyone? And do such efforts honor or distort the Founders’ vision?

It’s one thing to vote your values. That’s democracy. But it's another to legislate theology. That’s theocracy—and it’s precisely what the Constitution was written to avoid.

As Jefferson warned:

“It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”

(Jefferson, 1782)

Freedom of conscience, not enforced conformity, is the hallmark of American liberty.

Religion as a Living Tradition

America is a nation of many faiths—and no faith. Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, agnostics, and atheists all share the public square. Religion in America is not fading, but evolving. Churches coexist with yoga studios, synagogues with science labs, and mosques with town halls.

What binds us together is not shared belief, but shared rights: to speak, to assemble, to worship—or not—without coercion.

The beauty of this arrangement is that it allows religion to be powerful because it is personal. Forced faith is no faith at all.

Are We a Christian Nation?

So—are we a Christian nation?

Culturally, yes. Christian ethics helped frame our moral vocabulary. Our holidays, traditions, and civic norms reflect centuries of Christian influence. Our literature and politics are filled with biblical allusions and values rooted in Judeo-Christian tradition.

But politically and legally, no. We are a constitutional republic that explicitly forbids religious establishment. That is not a rejection of Christianity—it is a safeguard for it, and for every other belief system Americans hold dear.

Final Thoughts: Liberty for All

To claim the U.S. is a Christian nation in a legal or governmental sense is to misrepresent our founding principles. It also marginalizes millions of patriotic Americans who are not Christian but who contribute, serve, and uphold the very freedoms that allow religion to thrive.

The question isn’t whether America is a Christian nation. The better question is: Can America remain a free nation—where Christians, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, atheists, and everyone else are treated equally under the law?

The answer lies in honoring the Constitution and resisting the temptation to confuse influence with authority, faith with policy, and cultural tradition with constitutional design.